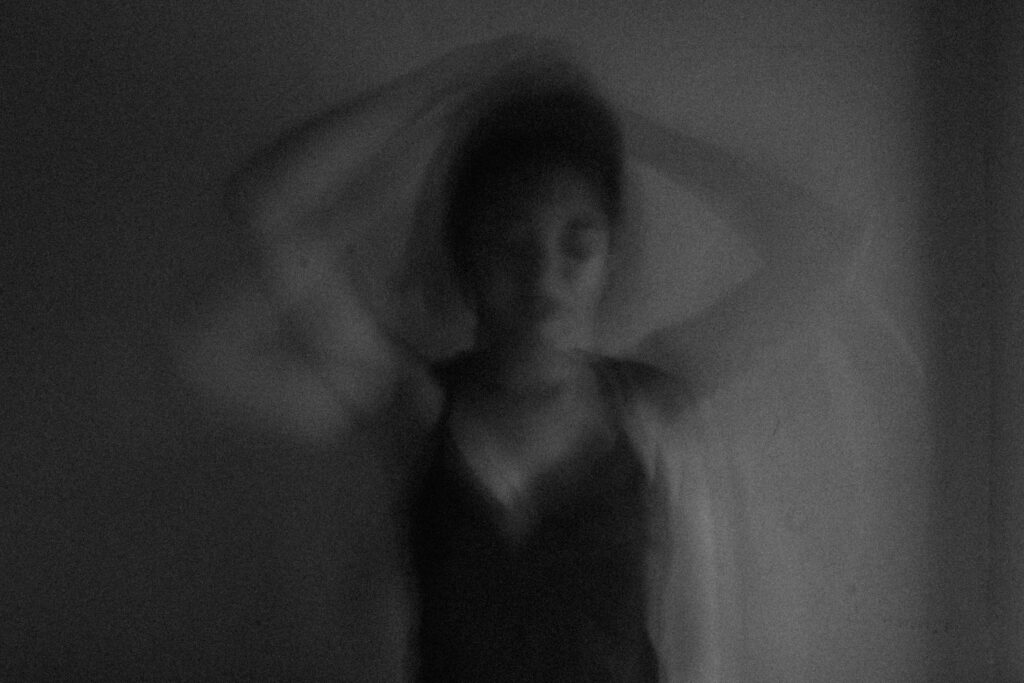

Unwomaned: Psychoanalytic Reflections on the Dehumanization of Women in Chaotic Times

Introduction

In times of war, displacement, sociopolitical collapse, and cultural repression, women are often among the first to lose their symbolic presence in society. They become unseen, unheard, and instrumentalized—objectified, commodified, or stripped of subjectivity. This process unfolds across diverse cultural, geographic, and historical contexts through sexual violence, reproductive control, and systemic silencing.

Psychoanalysis, rooted in the recognition of psychic reality and symbolic life, offers a framework for naming, containing, and witnessing these phenomena. It provides not only technique but also a transitional space for psychic integration amid collective trauma and moral collapse (Bion, 1962; Benjamin, 1990; Kristeva, 1989).

This reflection explores the psychological impact of female dehumanization, drawing from clinical observations and psychoanalytic theory. It further considers how analytic work can contain the unthinkable and support re-symbolization after trauma.

I. Clinical Vignette: The Silenced Body

A composite clinical image, derived from work with women in forced migration contexts, illustrates the psychic toll of dehumanization. One woman, in exile and in her late twenties, struggles to narrate her journey. Emotional expression manifests primarily through bodily symptoms—chronic pelvic pain, sensory numbing, and recurring nightmares.

“I don’t feel like a woman anymore,” she shares. “Just something people used.”

Here, trauma is inscribed somatically. Subjectivity has collapsed under the weight of unprocessed assault and loss. The analytic function—non-intrusive listening and offering language without appropriation—becomes a symbolic container. Gradually, metaphorical thinking re-emerges: “My voice is a lost child,” she reflects. Symbolization begins to return (Bion, 1962; Kristeva, 1989).

II. Modalities of Dehumanization

This process appears in diverse sociopolitical settings. While not exhaustive, the following categories highlight recurrent themes across clinical and humanitarian contexts:

Displacement and Migration: Women in precarious transit often face transactional sex, forced servitude, or erasure in asylum procedures, experiencing fragmentation, mistrust, and depersonalization (Volkan, 2001).

Militarized Conflict: Female bodies can become symbolic battlegrounds where sexualized violence, maternal grief, and social rupture inflict profound psychic wounds and intergenerational trauma (Scarfone, 2013).

Cultural Silencing: In some cultures, women’s voices are structurally suppressed through punitive responses to speech, dress, or dissent. This internalizes as shame, invisibility, and a sense of existential danger (Benjamin, 1990).

Domestic Violence in Crisis: Even in more stable societies, crises such as economic collapse or political instability can increase domestic violence, resulting in somatization, numbness, and agency collapse (Kristeva, 1989).

III. Psychological Sequelae

Psychoanalytic understanding identifies frequent patterns:

Dissociation and Somatization: Emotional overwhelm displaced into the body when mental processing is blocked (Bion, 1962).

Loss of Subjectivity: Women experience themselves not as agents but as functional objects—reproducers, caregivers, or victims (Benjamin, 1990).

Erosion of Trust: Interpersonal relationships become threatening after repeated violations or institutional betrayals (Volkan, 2001).

Transgenerational Echoes: Unspoken trauma impacts children through attachment ruptures and unconscious transmission (Scarfone, 2013).

IV. The Analytic Function in Times of Collapse

In such conditions, psychoanalysis offers rare psychic containment and recognition:

Containment: The analyst metabolizes overwhelming affect, rendering it more bearable (Bion, 1962).

Recognition: Affirming the patient’s experience preserves her sense of self as a subject (Benjamin, 1990).

Symbolization: Language transforms affect and experience into meaning (Kristeva, 1989).

Even in silence or fragmentation, the refusal to objectify supports rehumanization.

V. Comparative Contexts: Diverse Expressions of the Same Wound

| Context | Mechanism | Psychic Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Conflict regions | Sexual violence, kinship loss | Somatic pain, melancholia |

| Migration routes | Exploitation, identity erasure | Dissociation, fragmentation |

| Patriarchal cultures | Silencing, structural repression | Identity collapse, symbolic void |

| Economic collapse | Emotional control, domestic violence | Numbness, helplessness |

| Transgenerational loss | Cultural erasure, maternal grief | Disorganized attachment, despair |

VI. Conclusion: Re-Symbolizing the Female Subject

Dehumanization aims to strip symbolic life from the individual. Psychoanalytic work resists this erasure through witnessing, containing, and speaking ethically. The analytic space cannot undo violence or restore lost worlds—but it can bear memory, restore meaning, and slowly rebuild the capacity to feel, speak, and exist.

In chaotic times, such work becomes a quiet resistance: a labor of re-humanization through speech, relation, and presence. It is neither fast nor grand, but for the individual, it may mark the beginning of a return—not to what was lost, but to what still can become.

References

Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from Experience. Heinemann.

Benjamin, J. (1990). The Bonds of Love: Psychoanalysis, Feminism, and the Problem of Domination. Pantheon Books.

Kristeva, J. (1989). Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia. Columbia University Press.

Scarfone, D. (2013). The Unpast: The Actual Unconscious in Psychoanalysis. Routledge.

Volkan, V. D. (2001). Transgenerational Transmission and Chosen Trauma. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 82(5), 975–995.